- Home

- Alan Pearce

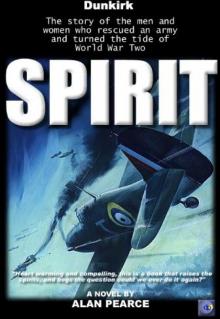

Dunkirk Spirit

Dunkirk Spirit Read online

Dunkirk Spirit

By Alan Pearce

Copyright 2011 e-eye digital editions

ISBN: 978-1-4581-1078-7

I wonder how many of you feel as I do about this great battle and evacuation of Dunkirk. The news of it came as a series of surprises and shocks, followed by equally astonishing new waves of hope. What strikes me about it is how typically English it is. Nothing, I feel, could be more English both in its beginning and its end, its folly and its grandeur.

J.B. Priestley, BBC Radio, June 5, 1940

Day One

06:57 Sunday 26 May 1940.

A Seaside Resort in Southern England

That was the Morning Prayer from Bristol, read by Doctor Simon Welch. Just a reminder before our first bulletin of news that later this morning at nine-twenty-five you can hear a special service from the City Temple here in London to mark today as the Day of National Prayer. The service will be read by the Reverend Leslie Weatherhead.

It was promising to be a fairly typical summer Sunday morning. The sky was leaden and low, the clouds racing towards the shore, and rain expected. But from her bedroom window on the third floor of a dilapidated Victorian seafront guesthouse Agnes saw something unexpected.

‘’Ere, love! You want to take a look at this.’ She turned to her husband who sat perched on the edge of the bed, his ear pressed to the wireless.

‘Shush, woman! Can’t you see the news is coming up?’

‘Well, if you ask me, it looks like there’s some news coming up, right out here.’

What Agnes saw was a lone Hurricane, a single-seater fighter, trailing clouds of white glycol fumes and flying soundlessly and at considerable speed just a few feet above the sea. And it was heading, if not directly for their guesthouse, then certainly for the beach below.

Inside the cockpit, Pilot Officer Neil Wood, with 260 hours’ flying time, was struggling with basic geometry. Having glided without power for the last fourteen minutes, he had hoped to retain sufficient altitude to skim over the rooftops and bring his damaged fighter down in the rolling fields behind the town. Unfortunately, with most of his instruments dead, including the altimeter, he had been obliged to estimate his height by looking out of the oil-flecked cockpit window at the waves below. Now he would have to drop swiftly and attempt a landing on the beach or else plough into one of the top floors of the sad-looking guesthouses that lined the seafront.

He adjusted the flaps to reduce speed. The Hurricane’s nose came up slightly in response, reducing his forward vision. With his speed now at less than one hundred miles an hour, the plane was preparing to stall. He cast a quick glance out of the cockpit to either side, and pulled back slowly on the spade-like control stick. The Hurricane began to settle backwards. He glanced again down at the waves, now just a foot or so beneath his wing. Instinctively, he checked his useless air speed indicator and then pushed the flaps fully down. He tugged urgently on the stick, pulling it back towards his chest, and braced for a tail-first landing.

He would never decide which was the most frightening: the spine-damaging vibration or the awesome sound of the Hurricane crashing through the waves and continuing on up the beach; thousands of egg-sized pebbles flying in all directions and the wooden propeller splintering as the aircraft ripped a deep furrow into the beach. It finally came to a stop, but first it spun sharply to the left like a stunt motorcycle and sent a further shower of stones and sand high up onto the promenade just six feet beyond the wingtip.

‘Fuck my boots!’ exclaimed the young Pilot Officer. It was a curious expression and one that he had picked up in the mess of his temporary squadron. He flopped back into his seat with overwhelming relief, having been thrown hard in his harness towards the instrument panel. Slowly he released his hands from their fierce grip on the stick. He flexed his fingers experimentally. He then flicked a lever and slid the canopy cover backwards, jettisoning the side flap. Next, he unfastened his harness, oxygen lead and radio plug, and then hopped out smartly, using the port wing as a springboard to launch himself onto the beach. He pulled his gloves off and tucked them under one arm.

A small audience looked down in amazement from the railings above. The young pilot took a bow. He then turned; suddenly interested to know where the Me109 had scored hits. He examined the engine cover first. A cannon shell had blown two valves away and punctured one of the glycol pipes where it joined the cylinders. This would explain the sudden rise in engine temperature before the pistons and block finally locked solid a few miles off the French coast. There were also several machine gun bullet-holes along the length of the fuselage. One had torn through the canvas skin just behind his seat. That would explain the huge bang when the oxygen bottle exploded. And that, in turn, would explain the high-pitched ringing tone in his right ear.

He didn’t hear the man approach.

‘Stick ‘em up and no funny business!’ The man jabbed viciously with a long wooden pole. It had a curved hook at the top, the kind used to pull down shop awnings. It knocked Neil in the small of the back. He turned suddenly.

‘Don’t you even think about it, you Nazi bastard! Got your comeuppance, good and proper. Now put your hands in the air or you’ll look like a bloody German sausage on a stick.’

‘German? German?’ queried the officer, indignant. ‘I’m not a bloody German.’ He reached up to his chin and slid off the leather flying helmet, goggles and oxygen mask. In the circumstances it was a foolish mistake.

‘Look how blonde he is! Just like those Nazis on the newsreels. Give us a goosestep, luv.’ A middle-aged woman in tight curls and a faded floral dress with stiff white apron had made her way down from the promenade. A small crowd followed in her wake.

Normally, he would have been happy to find himself described as blonde. Whilst he and his mother had always considered his hair to be fair, Neil had been plagued throughout his childhood and now into the RAF with the unfortunate nickname of Ginger. He was convinced that it was an effect of low-wattage light bulbs.

‘Don’t be ridiculous! I’m a Pilot Officer - Neil Wood of the Royal Air Force.’ And it hurt him to add: ‘People call me Ginger, not Blondie!’

‘That’s a laugh, ain’t it?’ The apron woman turned to gather support from the growing crowd. ‘He’s got a black uniform like those SS blokes, he’s blonde and he’s…’

‘And he’s gorgeous!’ Somebody else, a young married mother with her own blonde locks, called out from the back. ‘If all them Nazis look like him, they can come and…ouch!’ She received a sharp jab in the ribs from her own mother who stood beside her.

‘Eh! This ain’t right. He’s not got a RAF uniform on.’ A small boy of about ten years of age and wearing a home-knitted grey sleeve-less pullover had pushed his way to the front. He had a pudding basin haircut and he was tugging on Ginger’s left trouser leg. ‘The RAF blokes wear blue. Everyone knows that. Only Nazis wear black.’

Ginger examined his dark RAF flying suit beneath the hand-painted yellow lifejacket. His clothes were soaked through with perspiration. A heavy .45 Colt automatic protruded from his shoulder holster. His home squadron, based in the Midlands, had favoured black overalls. They could easily have chosen white from the varied air force stocks. Ginger had to admit that there could be an element of confusion. He also realised that it would be no help to unbutton the damp cotton overalls and show his uniform beneath. Aside from his flying boots, the only piece of identifiable RAF kit were his grey-blue trousers, but it would take ages to undo all the buttons, and it would not look dignified. He also wore a standard white roll-neck sweater but most people thought of RAF pilots, especially the dashing fighter crews, as wearing fur-lined Irvin leather flying jackets and sporting handlebar moustaches. They had seen them weekly on the Pathé newsreels

. But Ginger could only produce facial hair about once a week and then, being fair, the faint whiskers were barely noticeable.

‘And that ain’t no Spitfire, neither,’ said the kid, keen to keep up the momentum and his place at the head of the crowd.

‘No, it’s not a bloody Spitfire! Nobody said it was. It’s a Hurricane for your information, and those are bloody RAF markings. Twit!’ Ginger felt his face flushing. ‘You’re not very bright, are you sonny?’

‘That’s where you’re wrong, mister,’ the kid shouted back. ‘RAF markings don’t have yellow round ‘em. They’re red, white and blue. Everyone knows that.’ The crowd murmured agreement.

‘Oh, my God!’ said Ginger, exasperated. ‘It’s a new thing.’ He wondered why he was bothering to explain. ‘They’ve just added a bright yellow ring on the outside. It’s supposed to make the markings easier to identify.’

‘Yeah, right,’ explained the kid. Just then a uniformed policeman made his way across the beach. His step was measured and high, careful to avoid scuffing his brightly polished boots.

‘Bit of a bumpy landing that, sir. Are you all right?’ He cast a quick professional glance over Ginger, who nodded, and then turned to the crowd. ‘Now move along. Nothing else to see here. And let’s give this gentleman some breathing space, shall we?’ He spread his arms and the crowd fell back. He turned to Ginger, who tried to look grateful but only felt frustration.

‘I’ll just wait for my colleague to catch up and then we’ll take you down the station. You can have a nice cup of tea and then you can call your squadron.’

Ginger smiled. His mouth was bone dry. That tea sounded like a wonderful idea.

07:30 Sunday 26 May 1940.

Outskirts of Armentieres, near Lille, France.

‘Move your fucking arse!’ shouted Corporal Miller at the straggling line of Belgian refugees that blocked his path. He stabbed the accelerator of the quad truck and then jabbed the break as a warning that he was prepared to push his way through. A tall man in a grey overcoat and matching beret pushed with renewed vigour on the handle of his cart. Miller slipped the clutch and edged around to overtake.

The Service Corp depot had been situated in just about the daftest place possible. When it rained, which it had done for much of the winter, the main field that acted as the accommodation area became a vast lake that drew water from all the fields surrounding. The lorries, crates, boxes and containers remained relatively dry but, when the water turned to ice, it proved virtually impossible to move any of the stores up the faint incline that led to the main road. Now, by May, the field was awash in thick, slippery mud and it reminded many of the old hands of the surrounding Flanders fields of just twenty-two years before.

Miller used the mud to bring the truck to a slithering halt beside the Chaplain’s tent in an isolated corner of the depot. He pulled the key from the ignition and used his tongue to flick the cigarette-butt spinning. It landed near the feet of the Reverend Thomas Charlesworth, known simply as the Padre, an Army Captain and 4th Class Chaplain, temporarily attached to Number Two Supply Reserve Depot, Royal Army Service Corp, Lille. The Padre’s feet were encased in plastic galoshes. His Aunt Maud had chosen them from the Woolworth’s in Stony Stratford. She had been given the choice of either transparent pale blue or pale pink. She had decided that the pink was a better match for her nephew’s dull brown uniform. The Reverend Thomas Charlesworth only cared about keeping his feet dry. Miller thought the Padre looked like a pansy.

‘Where have you been?’ he demanded. A fine drizzle was beginning to coat the Padre’s weathered face. He opened his mouth to offer further chastisement but was interrupted by the hasty approach on foot of Major Featherstonehaugh, whose name was actually pronounced as Fanshaw. He was also known to one and all as a waste of space. He was breathing heavily and his face was red.

During the long winter months the men had held an unofficial “Guess the Major’s Weight” competition. The winning entry had been guessed correctly at eighteen-stone-eight-pounds. The winner had been Corporal Miller. He, in turn, was not known by the usual nickname of Dusty for men of that surname but as Ratman due to the sharp, rodent-like features of his face. The men, if asked about Miller, would say you could always judge a book by its cover.

‘Morning, Padre,’ puffed the Major. ‘I suppose you heard the news this morning?’

The Padre nodded. Everybody listened to the news.

‘They said the Frogs are inflicting heavy casualties on the Huns on all fronts. That’s bloody good news, isn’t it?’ He paused for breath. ‘But some of the chaps have just come back from Lille and they said you could hear the fighting in the distance, which means they can’t be far from here.’

‘There’s loads more activity on the roads, too, sir.’ Miller spoke up, even though it wasn’t his place. ‘And loads of bloody Flems all over the shop.’

Both the Padre and the Major turned and looked down at the corporal with distain. ‘Should you be standing here, doing nothing?’ asked the Padre. ‘We’ve Devine Service to sort out and this one’s rather important, at eleven-hundred-hours. So, chop, chop, Miller.’ Miller saluted like a guardsman and then slunk away to get a cup of tea and a wad from the NAAFI wagon.

The Padre took the Major by the arm and steered him inside the bell-tent. Unlike other officers of junior rank, the Padre was allowed his own private quarters. The Major, who shared his tent with a major in the intelligence section, eyed the dank and musty space enviously. The tent’s centrepiece was a Napoleonic-era campaign chest in dark mahogany and reinforced with sturdy lead bindings. There was a matching folding chair and camp bed. These were family heirlooms and on loan from his uncle in Stony Stratford.

‘Look here,’ he told the Major. ‘A word to the wise.’ He neglected to add ‘sir’. ‘I think it’s a lot more serious than that. I just heard that the Germans took Ghent and Courtrai yesterday and have now reached Calais.’

‘My God!’ stuttered the Major. ‘Well, that’s the first I’ve heard of it. Are you sure of your sources, Padre?’

‘As sure as anyone can be.’

‘My, God! Well, I’d better go and get things in order.’ He turned to leave. ‘Gosh, I’m a nit sometimes,’ he declared as he bent to exit the tent. ‘Jolly well forgot what it was I came here to tell you about.’

‘Yes?’ asked the Padre.

‘There’s another damn fifth column scare on. There’s a bunch of priest fellows being held down at the guardhouse. Probably German parachutists, if you ask me. But thought it best you come along and check their bona fides. We don’t want any more incidents with genuine nuns and whatnot being shot by mistake.’

10:25 Sunday 26 May 1940.

St. Peter’s Church, Aylesham, Kent

Pray for all who serve in the Allied forces by sea and land and air

Pray for peoples invaded and oppressed; for the wounded and for prisoners

Remember before God the fallen, and those who mourn their loss

’O Lord, let Thy mercy be shewed upon us

As we do put our trust in Thee

’O God the Father of Heaven

Have mercy upon us

There was a general chorus of Amen and the Reverend A.L. Bartlett closed the book, slipped the glasses to the end of his nose, and looked down upon his congregation. It was a good turnout. He hoped it would be reflected in the size of the collection. He could hardly believe his luck when His Majesty had announced on the wireless that this Sunday would be a Day of National Prayer. A full house indeed.

‘It is no mere territorial conquest that our enemies are seeking,’ the King had said with a trace of a stutter. ‘It is the overthrow, complete and final, of this Empire and of everything for which it stands: and after that, the conquest of the world.’

The Reverend coughed for emphasis. ‘Now, I have been asked to make a special announcement.’ He paused and looked around the congregation. ‘I have been asked by the local authorities to inform you that all school c

hildren are to be evacuated from coastal areas and nearby towns.’ He paused for the news to sink in. ‘Next Sunday. One week today.’ An audible sense of alarm rose from the congregation.

‘Now, the evacuation plans centre principally around the East and South Eastern towns on or near the coast, so you must take advantage of the arrangements to send your own children to safer districts in the Midlands and Wales. Registration will be opened immediately at the Town Hall and should be completed by lunchtime this coming Wednesday. That’s the twenty-ninth.

‘For additional details, Mr Maurice Healy, the Minister for Health, I’m told, is to give a talk on the subject tonight, after the Nine-O’clock News. I need not stress that it is of vital importance that parents register their children without delay. Otherwise they risked being left behind! Now, if you would turn to page number thirty-three in your hymnbook, Eternal Father, Strong to Save.’

Rose had hoped to get to the front of the queue for the reverend. Instead that awful Carmichael woman had beaten her to it. She watched as the woman droned on. Anyone could see that the reverend was keen to get away. Whilst the majority of the parishioners shuffled past, with nods and thank-yous, a small line was building up behind Rose. All were impatient and many sought advice. There was a lot of pent up passion and many would go home to their Sunday lunches with tight lips and little appetite.

‘Bloody stupid, stuck up cow,’ thought Rose. ‘Can’t she see she’s holding up the queue?’ She made a double ‘tut’ sound, loud enough to hear, and hugged her handbag closer to her chest. Rose’s hands were callused and red and the knuckles swollen and painful. There was going to be more rain, she could tell. She cast her eyes over Mrs Carmichael, who had gained weight since the Scouts’ bring-and-buy sale. ‘Bloody stupid, stuck up, fat cow.’ Rose was known for mumbling under her breath.

Dunkirk Spirit

Dunkirk Spirit