- Home

- Alan Pearce

Dunkirk Spirit Page 2

Dunkirk Spirit Read online

Page 2

‘Well, thank you very much, Reverend. Please call around any day in the week and collect them.’ Mrs Carmichael let go of the vicar’s hand. She turned to give Rose a cold nod and stepped out into the grey morning light and the wet pavements.

Although she would never show it, Mrs Margaret Carmichael was annoyed. With such an important event as the children’s evacuation, she had expected, at the very least, to be informed beforehand. She had been one of the main organisers when the first of the London evacuees were brought down in September the previous year to escape the bombs that had yet to fall. She had taken the dishevelled children door-to-door, seeking homes for them. She had organised winter clothing, and she had arranged the successful, although boisterous, Christmas party at the Snowdown Colliery Social Club. Now, with the growing fear of invasion, the children were on the move again, along with the villagers’ own, and she struggled to accept the fact that she had not been one of the first to know. It was unthinkable. She felt a deep onrush of irritation.

She walked through the town’s deserted market place and cast a glance at the bleak cement-fronted houses on either side. Her own house – tastefully early Victorian and detached - was just a short walk away. When she had arrived in the village just after the end of the Great War, there had been no village to speak of. Her husband, Dennis, had taken the position of colliery under-manager and had purchased the house outright. By the time Dennis took early retirement in 1926 the first foundations of the new town had been laid. And, just as the first of the new miners had moved in, Dennis had finally succumbed to the wracking cough from lungs slowly dissolving from the gas of the trenches. Margaret had been left alone and obliged, after a lengthy period of mournful isolation, to carve herself a role in the new community. The newfound desire to take control, to steer her life without Dennis, had led to an equal desire to steer the new town and to carve herself a role within it. She decided to go to the Town Hall personally, just as soon as she had had a cup of tea.

The telephone was already ringing when she put her key in the front door. Vicky, as per the usual instructions, answered the device in a clipped accent. ‘Mrs Carmichael’s residence. Vicky, the maid, speaking.’

Margaret placed her umbrella in the stand and turned quickly to the hall mirror to straighten her hair. She also gave her mackintosh a quick tug to straighten the lines. It was with a tone of ‘just as I expected’ that she took the receiver from Vicky and said: ‘Mrs Carmichael speaking. Who is this, please?’

Vicky lingered within earshot. Any day now she expected to hear about her application to join the WAAF, the women’s auxiliary air force. A posting to Singapore or some such exotic place where the boys would appreciate a nice fresh-faced English girl. The smart blue uniform, tightly belted at the waist, had been the deciding factor.

‘Yes, I have already had most of the details,’ said Mrs Carmichael in her own clipped accent.

11:18 Sunday 26 May 1940.

No. 2 Supply Reserve Depot, RASC, near Lille.

Despite their brilliant colouring, golden orioles are often difficult to see. They favour the tops of the trees and their markings of yellow and black provide a perfect camouflage amongst the foliage, especially on a sunny day. Although the skies were overcast, the Padre could only hear the glorious fluting call of the male. Somewhere in the distance he thought he could detect the answering cat-like squalling of a receptive female.

‘Don’t you think you ought to give it up as a bad lot, sir?’ asked Miller. ‘Don’t look like anyone’s going to attend now. If you ask me, they’ve all got a dose of the bloody wind up. Begging your pardon, sir.’

The Padre was inclined to agree. Two depressed-looking clerks constituted the only congregation. The Major, faithful to the Church as ever, sat on his own to one side, dabbing his nose with a large spotted snuff handkerchief.

The depot had been a hive of activity in the early morning but now it was quiet as the grave. Smoke from numerous small fires drifted in the distance. Only the birdsong and the leaves rustling in the trees kept at bay an overwhelming sensation of brooding doom.

The harsh puttering of a Bren gun carrier approaching from the tree line made everyone turn their heads. They waited for it to arrive.

Major Hewitt, the Headquarters Company commander, raised himself from the front seat of the tiny tank-like vehicle and waved urgently. It described a half-circle in front of the Padre and Miller before stopping in the mud.

‘Bloody hell, Padre! You still here?’ Hewitt stayed inside the open vehicle. ‘HQ says we’ve got to pull back towards Cassel. You should have been on your way two hours ago.’

‘What?’ exclaimed the Padre. ‘Nobody told me! And Cassel? That’s miles back. It’s halfway to the blinking coast. What’s the point in that?’

‘My, God!’ exclaimed the Major, who had shuffled over to the Bren gun carrier. ‘So you were right then, Padre. The bloody Huns have got the run of us. Some damn fool is going to find his head on the block for this one.’ He made a small ‘puff’ sound to show his indignation.

‘Better burn this lot, Padre.’ Hewitt waved his arm in the direction of the drumhead altar and the rows of folding benches.

‘Really? All of it?’ asked the Padre.

‘The whole bloody lot! Can’t let the enemy get hold of it.’

‘What? The prayer books, too?’

‘Especially those, Padre. If they fell into Nazi hands there’s no telling what they might do with them!’ He turned to Corporal Miller. ‘And you had better help the Padre pack up and then grab your rifle and make your way to the football field, pronto. Sergeant Warner is dealing with stragglers. He’ll tell you what to do.’

He nodded to the two clerks, including them. ‘And I am out of here. Got fish to fry, Padre. Can’t hang about. See you in Cassel, if we make it that far. Try the Hotel Faidherbe. Damn fine chops, if I remember rightly.’

With that, Major Hewitt tapped his driver twice on the helmet, saluted, and tore through the mud back to the tree line. The second Bren gunner on the anti-aircraft mount turned and waved a blank farewell.

‘Well, that’s us up shit creek without a canoe, if I’m any judge,’ said Major Featherstonehaugh.

The Padre turned and faced the altar. How was he supposed to destroy this lot? He considered praying for guidance, and then announced, ‘I think this would be a good moment for us all to pray.’ He knelt facing the altar and sensed that the tiny congregation behind him had done the same.

‘Dear Lord! Let us go forward to whatever lies before us with courage, fortitude and hope.’ The words came to him as if by divine inspiration. ‘The forces of evil may rage furiously, as the psalmist says, but, thank God, they cannot be triumphant.’ He clasped the Bible tightly to his chest and opened his eyes. ‘The Lord God omnipotent reigneth and one day His will will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Keep smiling and be cheerful, live close to God for underneath are the everlasting arms.’

‘Amen!’ said the Major. The Padre raised himself up and turned. The two men stood alone in the field.

‘Jolly good of you to give me a lift like this, Padre.’ They both looked out of the windscreen at the vast flock of sheep blocking the way. The Major sniffed again into his hankie. They had left the main route to Bethune, having found the road hopelessly clogged with refugees and with an alarming number of despondent French soldiers. They were now halted in a convoy of five British Army lorries down a narrow side road with the intention of reaching Estaires before nightfall.

‘It was a tough decision – not staying behind with the rearguard, and all, but well, you know, I’d make an easy target for some Hun.’ The Major had only stopped talking to pause for breath since leaving the depot three hours earlier. ‘Anyway, my skills are more in the logistics line, don’t you know.’

The Padre made another non-committal ‘mmm’ sound as he had to each rise in the Major’s inflection, indicating the end of a question or a statement requiring confirmation. But the Padre could only

think of two things. He was dreading seeing his aunt and uncle in Stony Stratford again. How was he going to explain the loss of the antique campaign chest and accompanying accoutrements? That was one problem. Another was what to do next.

The Padre’s military experience had been minimal. He had just managed to get into the Army at the tail end of the Great War, aged eighteen. But he had spent his entire service as a private reconditioning artillery pieces at Woolwich. He cast his mind back to the Bishop of Guildford, John Macmillan, and the awkward meeting on his return after five years in Australia.

‘You are a round peg in a square hole,’ the Bishop had told him. It was clear that his clerical superior was pleased with the description if not with the Reverend Charlesworth. ‘You are obviously a man of action. So here’s an idea for you.’ He went on to describe the excellent work that needed doing in the armed forces with war now a certainty.

‘So shall I take it that you will place your name on the Regular Army Reserve of Officers? There’s a desperate shortage of chaplains, you know.’

That had led to a simple medical and then a posting to the 1st Infantry Division, where he had been placed in charge of the officers’ mess. It was inappropriate preparation.

Suddenly, ahead of them, crews were jumping out of their lorries. They stumbled and fought they way through the bleating sheep and pushed themselves urgently on to the high grassy bank beneath the trees. The Padre and the Major both looked at each other for a moment and then did the same.

‘You would think that a group of dark lorries would stand out like a sore thumb, surrounded by all these white sheep,’ said the Padre.

They huddled close to the ground watching a second gruppe of Ju87s fly overhead at two thousand feet and disappear behind the trees. The black shapes were heading in the direction of the main road, the destination of the tiny convoy. They were all standing up, brushing bits of grass off their uniforms and looking sheepish themselves, when they heard the eerie sound of the Stukas’ sirens. Next came the sound of explosions and of machine-guns. It would be another hour before they would see the result of the Luftwaffe’s handiwork. And nothing in anyone’s previous experience could prepare them for what they saw.

Major Featherstonehaugh crouched on his knees, sobbing uncontrollably. He rocked slowly backwards and forwards and appeared to be hugging something tight to his breast. The Padre stood motionless, a look of abject horror on his face. How could he ever describe a scene like this to Aunty Maud and Uncle Henry? How could he ever tell anyone?

Dead people lay all about the road. Hundreds of them. Only here and there was there any evidence of life and what life there was appeared hideously mutilated. The length of the tree-lined boulevard was a mass of smoking debris, dead animals, twisted carts, burning cars and twisted people. The trees had been shorn of their leaves and now pieces of human meat hung from the branches. Bile rushed again into his throat. He quickly bent forward as the blood drained from his head and swirling stars filled his eyes. The Padre took a series of deep breaths and pulled himself erect. The next time he was asked if there were really a God he would wonder himself.

16:29 Sunday 26 May 1940.

Somewhere on the Escaut Canal, Belgium.

That was ‘Widder Patten Speaks her Mind’, a short story written for broadcasting by S.L. Bensusan and read by the author. Now, before we hand over to Dudley Beavan at the organ of the Granada, Cheam, here is a public service announcement on behalf of the War Office. Twelve bore shotgun cartridges are wanted for distribution to Local Defence Volunteers. The Commander-in-Chief Home Forces requests all people who have these cartridges to hand in as many of them as possible to the nearest police station.

Brigadier Merton Beckwith-Smith, commanding the First Guards Brigade, and known affectionately as Becky, was a self-proclaimed expert on the Ju87 Stuka dive-bomber and he was always ready with helpful advice.

‘Stand up to them. Shoot at them with a Bren gun from the shoulder,’ he told the perplexed gun crew as they stood to rigid attention beside their wet trench. ‘Take them high like a high pheasant. Give them plenty of lead and remember, five pounds to any man who brings one down. I have already paid out ten pounds.’

The Brigadier waved his swagger stick by way of salute. ‘And good luck.’

He turned to Lieutenant Alexander Mackenzie-Knox, an affable young Coldstream Guards officer, and took him gently by the arm, away from the men.

‘Keep your eyes open, Sandy.’ He smiled kindly at his subordinate and wondered if he would see the fellow in the morning. ‘Our reconnaissance bods think the Jerries will try to break through somewhere in this sector. The Belgians are on the verge of cracking and the French don’t seem to know whether they’re coming or going.’ He winked; the traces of a wicked grin reflected in his red eyes. ‘In the meantime, Jerry has had time to lick his wounds, refuel his panzers and generally get his show back on the road. I’m entrusting you with this bridge, Sandy. It’s up to us now to stop them. And they must be stopped here. I know I can count on you.’ The Brigadier turned now towards the adjutant.

‘Peter, here, will give you all the details. I must pop along and see how Jumbo’s doing.’

The staff Humber roared off.

‘Right,’ said Peter. ‘That RE chap has finished his work on the bridge. But you will give the order to blow it the moment you see fit. There’s a party of engineers on the other side. Make sure you give them a chance to get back first. Three smart toots on the whistle. Do not, repeat, do not let the Bosche get hold of this bridge. All clear?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, if there are no more questions, I’ll give Sergeant Harris his instructions.’ The sergeant, who was already standing to attention, called out, ‘Sur!’ in a voice loud enough to be heard either side of the canal.

‘Sergeant, do you have a revolver?’

‘No, sir. Just a rifle, sir.’

‘Mmm,’ said the adjutant. ‘Well, make sure it’s loaded and listen carefully. The very instant Mr Mackenzie-Knox attempts to sit or lie down, you are to shoot him. Do you understand?’

The sergeant patently did not understand and he hesitated before shouting, ‘Sur!’

‘Just a minute, Peter,’ put in Sandy hastily. ‘Surely…’

‘Shut up, Sandy. Look, we are all dog-tired. I don’t known when I last had a proper sleep longer than three minutes and you look twice as knackered as I do. The instant you stop to sit down, you’re going to nod off. So, sergeant, repeat my instructions.’

‘I’m to shoot Mr Mackenzie-Knox the very instant he sits or lies down, sur.’

‘Right, if I find Mr Mackenzie-Knox alive and asleep when I next come by, you will know what to expect. Good luck!’

For the rest of the afternoon, nobody in 11 Platoon dared sit down. Sandy was even cautious about approaching walls or trees too closely in case Sergeant Harris thought he might lean against them. He had sited two Bren guns on the opposite bank, either side of the ancient stone bridge, and issued instructions that the refugees were to be screened carefully before letting them across one at a time. Special attention was to be given to anyone dressed as a priest or nun.

The tide of fleeing Belgian civilians had been fairly constant for much of the day. But, by late afternoon, the numbers began to dwindle and Sandy, totally fed up with watching them stagger across the canal, thought to write to his brother.

‘I’m only leaning my papers on the tailgate, Sergeant,’ said Sandy as he cautiously approached the 15cwt officer’s truck. The Sergeant nodded his approval and lowered the rifle. Sandy sucked the nib of his pen and wondered what he could write about. His brother, Digby, was known as Badger because he was always trying to persuade people to do things, like come and play tennis, or walk around the loch. He had a hush-hush job at the British Embassy in Buenos Aires where, no doubt, he organised numerous bridge and croquet parties.

Sandy wondered if he should tell Badger about the cow he had shot that morning. A small herd had ap

proached the opposite bank just after dawn and had made the most frightful noise. The men had all agreed that they needed milking, having been abandoned by their owners several days prior, but none of the men knew how to do it. One of the cows had then slipped down the bank but, because of the mud, had been unable to get back up again. It had then spent about two hours feverishly swimming from one bank to the other, mooing at the top of its voice. Sandy had finally snapped and grabbed his rifle. The cow was now wedged against one of the bridge supports and had been swelling throughout the day. Sandy decided that he wouldn’t write about the cow.

He wanted to tell Badger about the events of the past few days, especially the fact that he hadn’t had a proper wash since the middle of the previous week. That had been his last hot meal, too. And, because of the total shortage of reliable drinking water, he wanted to tell how he had been obliged to shave in champagne for the officers’ conference the previous evening. Then there was the endless marching from one place to another. The holes they had dug and then not used before pulling back yet again. And the total lack of sleep. During the winter he had queried the need to practice so many rearguard and withdrawal exercises.

‘We always start a war with a major retreat – Corunna, Mons – to name just two,’ Major Stephenson, Battalion intelligence officer and history buff, had told him. ‘What makes you think it will be any different this time?’

He could hardly write to his brother about that. Sandy put the top back on his pen and stepped cautiously away from the truck.

The day was beginning to draw in, the rain had picked up again, and the Royal Engineers had reached the far bank. Their officer, a fresh-faced lieutenant, waited until all his men were across, and then ran at the double. Sandy met him by the roadside. ‘Nice day for it,’ said the newcomer, pausing briefly for breath. ‘I know it’s none of my business, but you might want to think about getting your blokes back to this side pretty soon. We’ve been hearing Jerry armour for the last hour or more.’

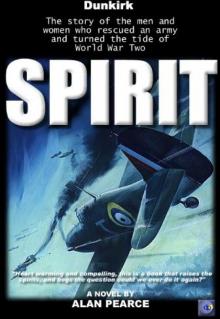

Dunkirk Spirit

Dunkirk Spirit